The Hematite Morin Transition#

Source of text

This text on the Morin transition is from the Spring 2010 issue of the IRM Quarterly Bowles, Julie; Jackson, Mike; Banerjee, Subir. (2010). IRM Quarterly, Volume 20, Number 1 (Spring 2010). Cover article: Interpretation of Low-Temperature Data Part II: The Hematite Morin Transition. Retrieved from the University Digital Conservancy, https://hdl.handle.net/11299/171318. with minor edits by Nick Swanson-Hysell.

Hematite (αFe₂O₃; Fig. 11) is a common mineral in many natural samples, and its presence is often easy to recognize via its high coercivity and high unblocking temperatures (just below 675 °C). However, in some cases a non‐destructive method may be preferred, in which case identification of the Morin transition [Morin, 1950] at ~262 K (–11°C) is diagnostic of hematite. Natural samples at high elevations or latitudes may cycle many times through the Morin transition, so an understanding of what happens to magnetic properties at this temperature is important for paleomagnetic interpretations.

Fig. 11 Scanning electron microscope image of hematite. Image is ~800 μm across. Source: Wikimedia Commons.#

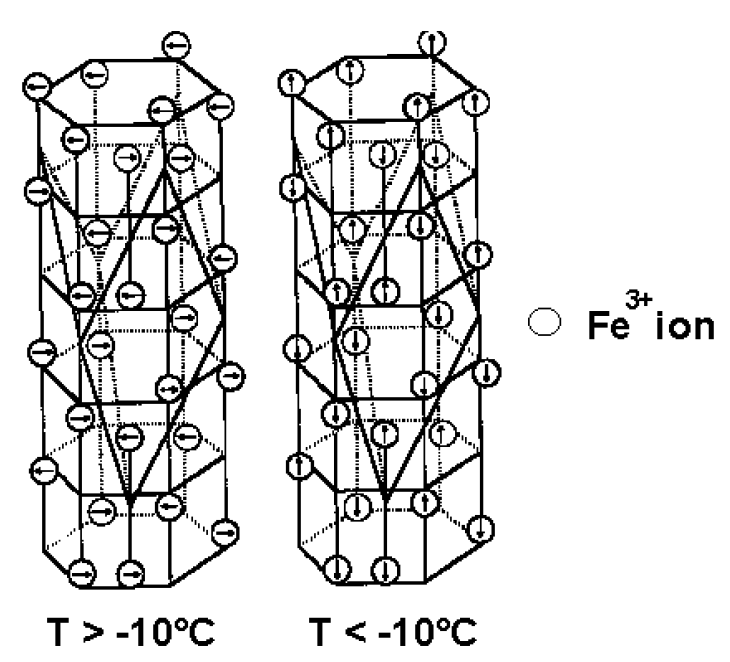

The basic magnetic structure of hematite is antiferromagnetic; its two magnetic sublattices have equal moment. However, at temperatures above the Morin transition temperature (TM), the spins are not perfectly anti‐parallel, and a slight canting leads to a weak, “parasitic” ferromagnetism in the basal plane, perpendicular to the hexagonal c-axis. At T = TM, magnetocrystalline anisotropy changes sign, the easy axis of magnetization shifts, and the spins rotate from the basal plane into alignment with the c-axis at T < TM (Fig. 12). The sublattice spins are then perfectly anti‐parallel, and the parasitic moment disappears. The only remaining remanence arises from defects in the crystal structure (a “defect ferromagnetism”).

Fig. 12 Crystal structure of hematite. Above the Morin transition (left), spins are in the basal plane perpendicular to the rhombohedral c-axis, and a weak ferromagnetism arises from spin canting. Below the Morin transition (right), spins rotate parallel to the c-axis and are perfectly antiferromagnetic. Image after Fuller [1987] and from the Hitchhikers Guide to Magnetism [Moskowitz, 1991].#

The exact temperature of the Morin transition is dependent on a number of variables: grain size, cation substitution, lattice defects (which lead to strain), pressure, and applied field. For pure, stoichiometric hematite at ~1 atm, TM ≈ 262 K [Morrish, 1994]. A weak grain size dependence from ~10,000 µm to ~0.1 µm results in a suppression of TM by only ~10 K (to 250 K) at the small end of this range [Özdemir et al., 2008; and references therein]. For grains smaller than ~0.1 µm, TM is strongly dependent on grain size and decreases dramatically, from ~250 K at 0.1 µm, to 190 K at 30 nm, and to < 5 K at 16 nm [Özdemir et al., 2008]. The suppression of the Morin transition temperature in nano-hematite arises in part from high internal strain [e.g. Schroeer and Nininger, 1967; Muench et al., 1985] and from a large surface to volume ratio, which allows surface effects to dominate spins [e.g. Kündig et al., 1966].

Cation substitution will also suppress TM; 1 mol% Ti substitution will suppress TM to < 10 K [e.g. Morin, 1950; Curry et al., 1965; Ericsson et al., 1986]. Other cations (with the exception of rhodium, ruthenium and iridium), as well as lattice defects, produce similar effects [Morrish, 1994]. The presence of a magnetic field will also decrease TM [e.g. Besser and Morrish, 1964; Özdemir et al., 2008; Morrish et al., 1994 and references therein]; the effect is roughly linear in fields < ~3 T, lowering TM by ~6 K/T.

Significant increases in TM can be induced via hydrostatic pressure, with estimates of the variation ranging from ~10 K/GPa to ~37 K/GPa [e.g. Bruzzone and Ingalls, 1983; Umebayashi et al., 1966; Worlton et al., 1967]. Thus, at room temperature the “spin-flop” transition may be brought about by application of pressures in the range of ~2 GPa [Morrish, 1994], although with increasing pressure, the transition may be less abrupt. Conversely, the application of uniaxial stress results in decrease in TM [Allen, 1973]. In contrast, to static, in-situ pressure experiments, samples that have undergone shock treatments have reduced Morin transition temperatures, likely as a result of reduced grain size and increased crystal defects [Williamson et al., 1986].

Finally, we note only in passing that annealing of samples frequently results in both an increase of TM and a sharper transition, resulting from reduction in defects, crystal growth, or both [e.g. Dekkers and Linssen, 1989].

Remanence Data#

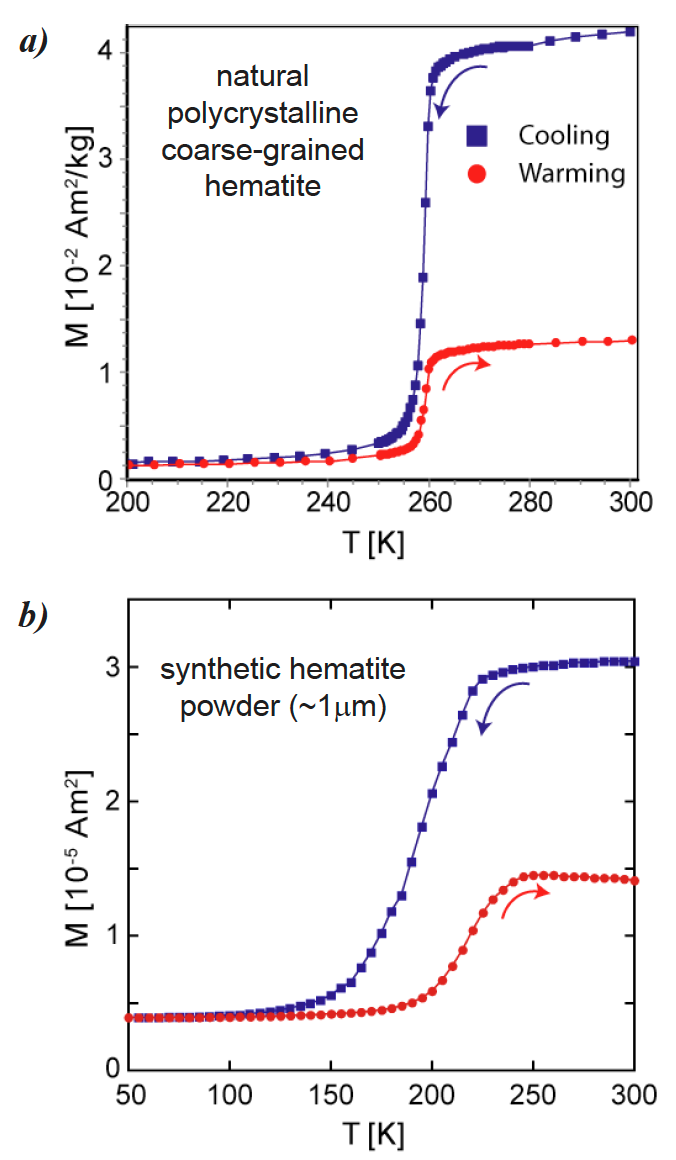

On cooling through the Morin transition, the parasitic ferromagnetic remanence will rapidly decrease (Fig. 13), leaving only the (typically) much smaller defect moment. On warming back through TM, remanence is partially recovered. Özdemir and Dunlop [2005; 2006] proposed that this remanence “memory” arises from small zones of canted spins (pinned via crystal defects) that do not fully rotate into the alignment with the c-axis below TM. These zones serve as nuclei for the re‐establishment of remanence on warming back through TM even in a zero‐field environment. The percent recovery on warming is not strongly correlated with grain size, but instead scales with the magnitude of the defect moment at T < TM [Özdemir and Dunlop, 2006]. However, Kletetschka and Wasilewski [2002] find a minimum in remanence recovery associated with a grain size near the SD–MD transition (~100 µm).

Fig. 13 Low-temperature cycling of a room-temperature IRM. On cooling through TM, magnetization decreases to near zero as the spins become perfectly antiferromagnetic. Small regions of canted spins likely remain at low temperature, explaining the recovery of remanence on warming in zero field [Özdemir and Dunlop, 2006]. (a) A natural, coarse-grained hematite with TM ≈ 260 K and very little thermal hysteresis. (b) A synthetic, relatively fine-grained hematite powder with a suppressed TM (occurs at lower temperatures) and significant thermal hysteresis (with recovery of magnetization at a higher temperature upon warming than its loss upon cooling). Note that the temperature scales in (a) and (b) are different.#

Thermal hysteresis in the Morin transition is frequently observed in the low‐temperature cycling of an IRM; the transition occurs at lower temperatures on cooling than on warming. This thermal hysteresis is not due to temperature lag in the sample, but is expected in a first‐order phase transition such as the Morin transition. While hysteresis is seen in almost all samples, Özdemir et al. [2008] note that a larger temperature difference between cooling and warming (ΔTM) is typically seen in samples with a smaller grain size and/or higher defect density. The effect is not strong in the relatively coarse‐grained natural hematite shown in Fig. 13. By contrast, a decreased TM and increased ΔTM are clear in a relatively fine‐grained (~1 µm) synthetic hematite powder sample (Fig. 13b).

Low-Field Susceptibility Data#

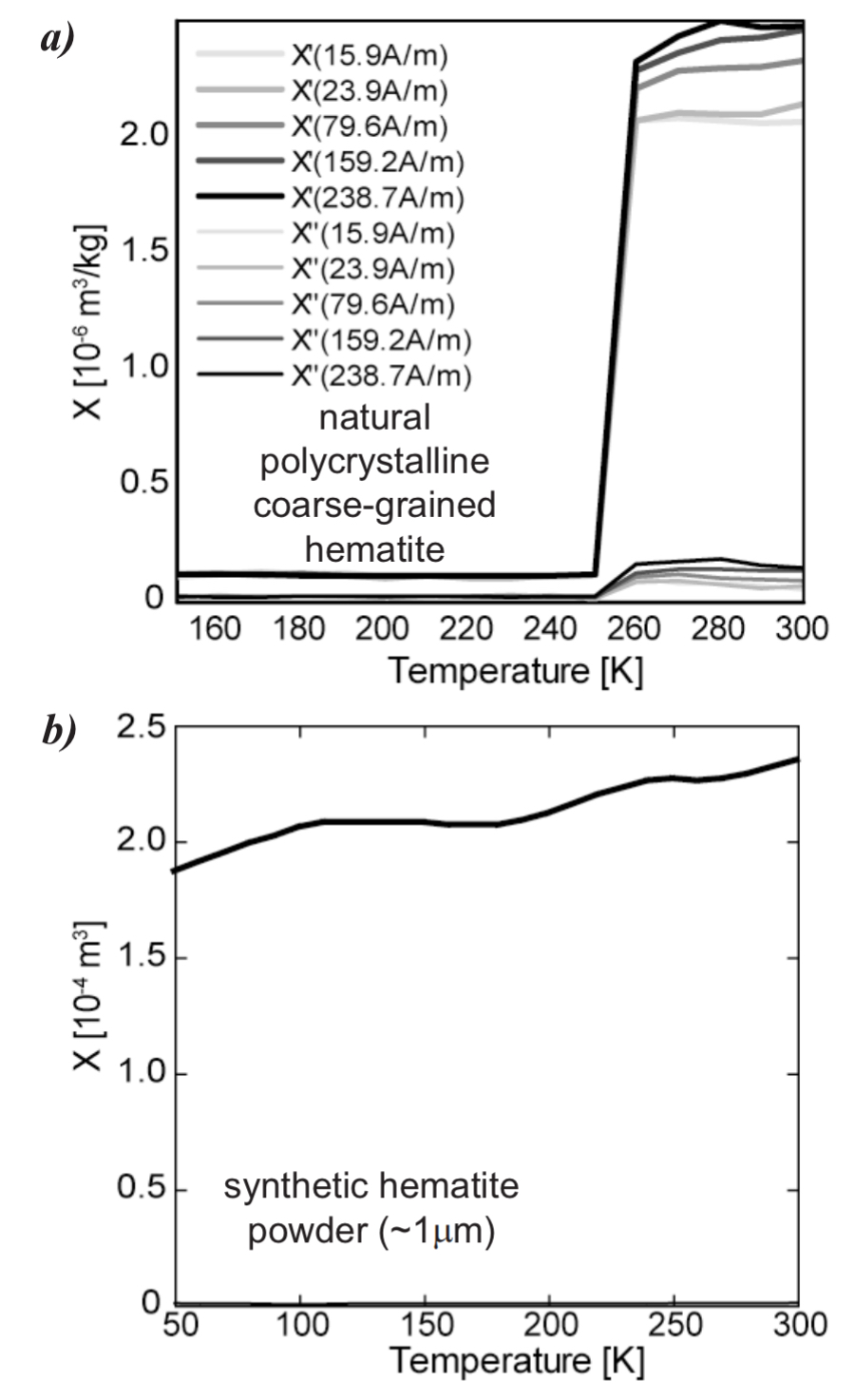

Above TM, low-field susceptibility is strongly dependent on crystallographic orientation; there is a weak, 3-fold anisotropy in the basal plane, and susceptibility is much lower parallel to the c-axis (e.g., Hrouda, 1982). Below TM, the antiferromagnetic susceptibility in the basal plane is about two orders of magnitude lower than above TM and decreases with decreasing temperature. In contrast, susceptibility parallel to the c-axis remains nearly constant from T = 0 K to the Néel temperature of 948 K, with a small increase at TM [Stacey and Banerjee, 1974]. In samples with randomly oriented hematite grains, the susceptibility decreases on cooling to a small fraction of its room-temperature value at T < TM (this neglects any contribution from the defect moment, which can be considerable). In practice, samples display a wide range of susceptibility decreases across TM – dropping to ~5% of the room-temperature susceptibility for coarse-grained samples with only a minor decrease for synthetic powders with ~1 µm-sized particles (Fig. 14b).

Fig. 14 In phase (Χ′) and out-of-phase (Χ″) susceptibility. (a) Susceptibility decreases dramatically at T < TM in a natural, coarse- grained hematite. Above TM, the field-dependence of susceptibility is characteristic of many multi-domain minerals. (b) In a relatively fine-grained hematite, TM is suppressed to ~200 K. Susceptibility also changes very little across TM in contrast to remanence data (Fig. 13b). Note temperature scales in (a) and (b) are different.#

Morin Transition Imposters#

We briefly note a common Morin transition imposter. When measuring wet sediments, grain reorientation can occur as water freezes (at ≤ 273 K), resulting in a drop in remanence that is occasionally misinterpreted as the Morin transition.

It is also possible for hematite to masquerade as magnetite. In nano-hematite or cation-substituted hematite, the Morin transition temperature can be significantly suppressed such that a transition around ~20 K in a room-temperature remanence may be mistaken for the magnetite Verwey transition. The two can be distinguished by the fact that magnetite should acquire a significant magnetization at low temperatures, whereas hematite will not.

References#

Allen, J.W., Stress dependence and the latent heat of the Morin transition in Fe₂O₃, Phys. Rev. B., 8, 3224–3228, 1973.

Besser, P.J., and A.H. Morrish, Spin flopping in synthetic hematite crystals, Phys. Lett., 13, 289–290, 1964.

Bruzzone, C.L., and R. Ingalls, Mössbauer-effect study of the Morin transition and atomic positions in hematite under pressure, Phys. Rev., 28, 2430–2440, 1983.

Ericsson, T., A. Krisnhamurthy, and B.K. Srivastava, Morin-transition in Ti-substituted hematite: A Mossbauer study, Physica Scripta, 33, 88–90, 1986.

Curry, N.A., G.B. Johnston, P.J. Besser, and A.H. Morrish, Neutron diffraction measurements on pure and doped synthetic hematite crystals, Phil. Mag., 12, 221–228, 1965.

de Boer, C.B., T.A.T. Mullender, and M.J. Dekkers, Low-temperature behavior of haematite: Susceptibility and magnetization increase on cycling through the Morin transition, Geophys. J. Int., 146, 201–216, 2001.

Dekkers, M.J., and J.H. Linssen, Rock magnetic properties of fine-grained natural low-temperature haematite with reference to remanence acquisition mechanisms in red beds, Geophys. J. Int., 99, 1–18, 1989.

Kletetschka, G., and P.J. Wasilewski, Grain size limit for SD hematite, Phys. Earth Planet. Int., 129, 173–179, 2002.

Kündig, W., H. Bömmel, G. Constabaris, and R.H. Lindquist, Some properties of supported small α-Fe₂O₃ particles determined with the Mössbauer effect, Phys. Rev., 142, 327–333, 1966.

Morin, F.J., Magnetic susceptibility of α-Fe₂O₃ and α-Fe₂O₃ with added titanium, Phys. Rev., 78, 819–820, 1950.

Morrish, A.H., Canted Antiferromagnetism: Hematite, World Scientific, River Edge, NJ, 192 pp., 1994.

Moskowitz, B.M., Hitchhikers Guide to Magnetism, prepared for Environmental Magnetism Workshop, Minneapolis, 1991.

(available at: http://www.irm.umn.edu)

Özdemir, Ö., and D.J. Dunlop, Thermoremanent magnetization of multidomain hematite, J. Geophys. Res., 110, B09104, doi:10.1029/2005JB0003820, 2005.

Özdemir, Ö., and D.J. Dunlop, Magnetic memory and coupling between spin-canted and defect magnetism in hematite, J. Geophys. Res., 111, B12S03, doi:10.1029/2006JB004555, 2006.

Özdemir, Ö., D.J. Dunlop, and T.S. Berquó, Morin transition in hematite: Size dependence and thermal hysteresis, Geochem. Geophys. Geosys., 9, Q10Z01, doi:10.1029/2008GC002110, 2008.

Schroeer, D., and R.C. Nininger, Morin transition in α-Fe₂O₃ microcrystals, Phys. Rev. Lett., 19, 623–634, 1967.

Stacey, F.D., and S.K. Banerjee, The Physical Principles of Rock Magnetism, Elsevier, New York, 195 pp., 1974.

Umebayashi, H., B.C. Frazer, and G. Shirane, Pressure dependence of the low-temperature magnetic transition in α-Fe₂O₃, Phys. Lett., 22A, 407–408, 1966.

Worlton, T.G., R.B. Bennion, and R.M. Brugger, Pressure dependence of the Morin transition in α-Fe₂O₃ to 26 kbar, Phys. Lett., 24A, 653–655, 1967.

Williamson, D.L., E.L. Venturini, R.A. Graham, and B. Morosin, Morin transition of shock-modified hematite, Phys. Rev. B., 34, 1899–1907, 1986.